To analyze the dynamics of an orb descending from an elevated point, begin with the principles of free fall. The absence of air resistance simplifies calculations, allowing for a straightforward application of gravitational acceleration, which is approximately 9.81 m/s². This constant governs the descent speed, accelerating the object uniformly as it travels downward.

Determine the height of the ledge. For instance, if the edge is 45 meters tall, use the formula to find the time it takes for the object to hit the ground. The equation (t = sqrt{frac{2h}{g}}) provides the time in seconds, where (h) is the height and (g) is gravitational acceleration. Plugging in the values gives a clear prediction of the descent duration.

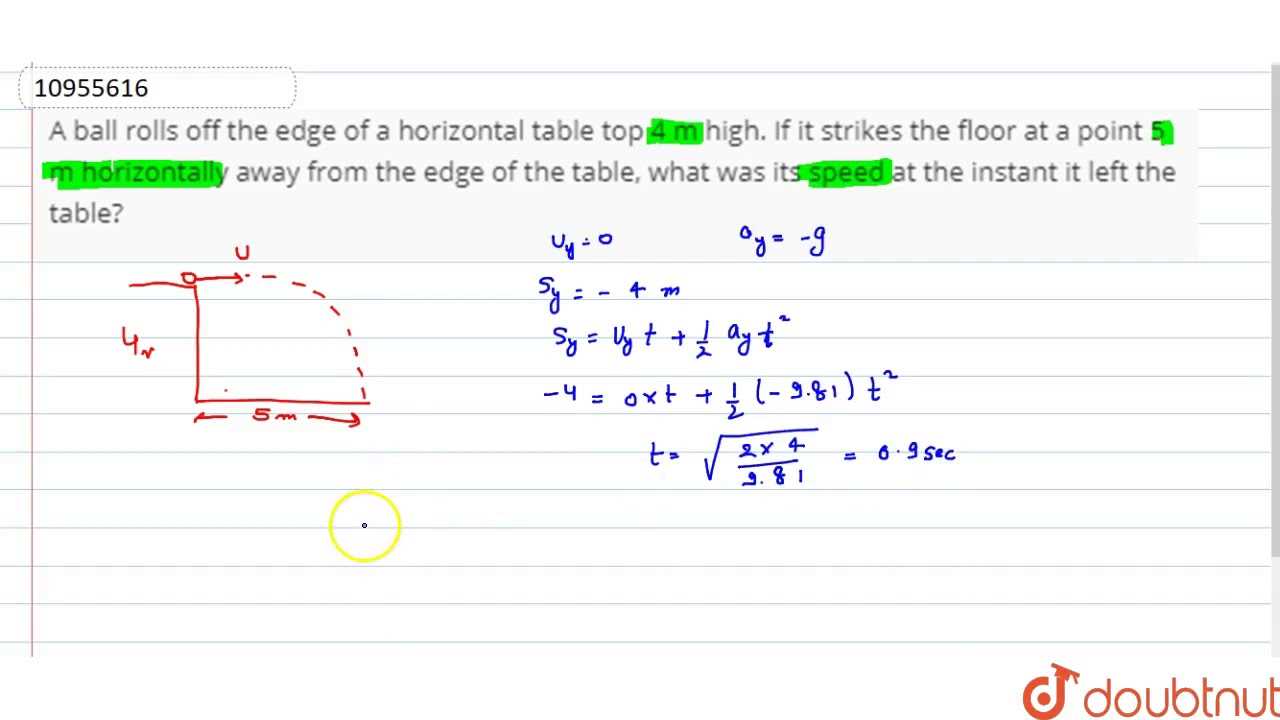

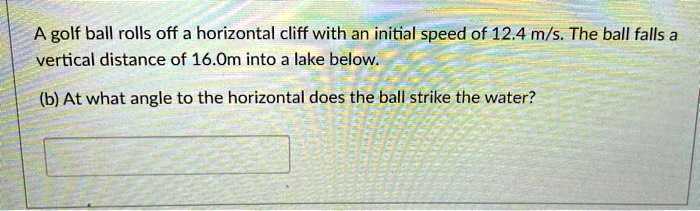

Consider the initial horizontal velocity if the object is propelled before the fall. This modifies the trajectory, resulting in a parabolic path. The horizontal distance traveled can be calculated using (d = vt), where (d) is distance, (v) is initial horizontal speed, and (t) is the time calculated earlier. Such calculations reveal not only how far the orb travels but also how variables such as wind resistance could affect its motion.

A Golf Sphere Descends from an Elevated Edge

Upon disengaging from an elevated surface, the spherical object exhibits a distinct behavior governed by gravitational forces. Its trajectory can be predicted using basic physics principles, particularly the laws of motion. The descent duration is determined by initial conditions such as height and the absence of air resistance. An object released from a height of, say, 20 meters, will reach the ground in approximately 2 seconds, irrespective of its horizontal velocity.

Factors Influencing the Trajectory

Key considerations include the angle of descent and horizontal velocity at the moment of release. The combination of these parameters creates a parabolic path. For example, if the object has an initial horizontal speed of 5 meters per second, this velocity remains constant while gravity accelerates the object downward at 9.81 meters per second squared. The impact point can therefore be calculated through simple kinematic equations, aiding in predictions regarding landing locations.

Practical Applications and Observations

This phenomenon is not just theoretical; it finds application in various sports and engineering. Understanding the motion allows athletes to tailor their strategies and engineers to design safer structures. Observations in sports reveal that refining launch angles and velocities can significantly enhance performance outcomes, underscoring the relevance of physics in real-world scenarios.

Understanding the Physics of Free Fall

To analyze the motion of an object in free fall, start by acknowledging the influence of gravity as the sole force acting on it after it has separated from a surface. Gravity accelerates the entity downward at approximately 9.81 m/s².

Key points to consider:

- The time taken to hit the ground can be calculated using the formula: t = √(2h/g), where h represents height and g is the acceleration due to gravity.

- Velocity at impact is determined by: v = g * t. This formula helps predict how fast the object will travel just before contacting the ground.

- Horizontal distance traveled before reaching the ground can be computed as: d = v₀ * t, where v₀ is the initial horizontal velocity.

During descent, air resistance can influence the object’s motion, especially if it has a high surface area relative to its mass. However, for smaller or denser objects, this effect is often negligible compared to gravitational force.

Consideration of initial conditions is essential. If an object is projected horizontally versus dropped vertically, both scenarios will yield different trajectories despite the same gravitational influence.

Factors like wind and altitude may introduce variability, particularly in larger structures or during significant falls. Conduct experiments to measure how these factors alter fall characteristics for precise outcomes.

In summary, applying basic physics principles allows for accurate predictions of motion when an object is subjected solely to gravitational forces. Understanding these principles is fundamental in physics, engineering, and various applied sciences.

Calculating the Distance Traveled by the Object

To find out how far the object moves horizontally before reaching the ground, first determine the height (h) from which it is released. Use the formula for the free fall time:

t = √(2h/g),

where t is the time in seconds, h is the height in meters, and g is the acceleration due to gravity (approximately 9.81 m/s2).

Once you have calculated the time of fall, measure the horizontal velocity (v). This velocity remains constant throughout the descent because no horizontal forces (ignoring air resistance) act on the object. The distance (d) traveled horizontally can then be calculated with:

d = v * t.

Substituting the calculated time into this equation provides the total horizontal distance covered before impact.

For example, if the height is 20 meters and the horizontal velocity is 5 m/s, first find the fall time:

t = √(2*20/9.81) ≈ 2.02 seconds.

Then, calculate the horizontal distance:

d = 5 * 2.02 ≈ 10.1 meters.

In this scenario, the object would travel approximately 10.1 meters before hitting the ground.

Factors Influencing the Object’s Trajectory

The path taken by a spherical projectile after detachment from a ledge is primarily governed by initial velocity, gravitational force, and aerodynamic properties. Each of these elements plays a pivotal role in shaping the overall trajectory.

Initial Velocity

The speed and direction at which the object exits the edge significantly affect its eventual landing position. A greater initial velocity increases the distance traveled horizontally before reaching the ground. Variations in the angle of release can alter the trajectory, as higher angles lead to increased altitude but potentially decreased horizontal distance. The force applied during the object’s departure must be accurate for the desired outcome.

Aerodynamic Properties

Air resistance impacts the movement of the object in flight. Factors such as surface texture and shape determine how much drag the object experiences. Smoother surfaces reduce drag, resulting in a longer travel distance. Furthermore, the mass of the sphere plays a role; a heavier object will be less affected by air resistance and maintain its momentum more effectively.

| Factor | Impact on Trajectory |

|---|---|

| Initial Velocity | Directly affects horizontal distance; higher speeds yield greater travel. |

| Angle of Departure | Alters height and overall distance; optimal angles offer the best results. |

| Aerodynamic Shape | Influences drag; streamlined forms enhance range. |

| Mass | Affects resistance to air; heavier objects experience less deceleration. |

Effects of Wind and Air Resistance on Motion

Wind significantly alters the trajectory of an object in motion. The direction and speed of the wind can cause deviations from the expected path, requiring consideration during analysis. For an object in free fall, even a slight breeze can result in measurable lateral displacement.

Air resistance plays a vital role in affecting velocity. As the object descends, it encounters drag force which opposes its motion. This force is proportional to the object’s speed and cross-sectional area. Larger areas increase drag, slowing descent. Aerodynamic shapes reduce resistance, facilitating a more efficient fall.

The interplay between wind and air resistance can be quantified through drag coefficients, which depend on shape and surface texture. Accurate measurements of these coefficients allow for predictive modeling of how far and fast an object travels before reaching the ground.

Understanding these dynamics is essential for precise calculations. Wind conditions must be measured and factored into descent equations to assess total displacement accurately. Adjustments based on atmospheric conditions lead to more reliable predictions of motion, especially in outdoor settings.

Practical Applications in Golf and Ballistics

The study of motion under gravity can greatly enhance performance in various activities, particularly in structuring launching techniques for sports or projective strategies in military applications. Understanding the dynamics involved can lead to strategic improvements.

Optimizing Launch Angles

Knowledge of free fall mechanics helps determine the ideal angle of release for achieving maximum distance in a sporting context. An angle of approximately 45 degrees is statistically proven to maximize horizontal travel under ideal conditions. Adjusting this angle based on environmental factors such as elevation and wind speed can further optimize outcomes.

Ballistics and Trajectories

In the field of ballistics, comprehension of gravitational effects and projectile motion is crucial. Accurate calculations of trajectory ensure that munitions hit their intended targets consistently. The principles applied in the analysis of motion can translate to both enhancing accuracy and improving safety measures during target practice.

Furthermore, engineers developing ammunition can utilize physics to optimize projectile design for varied conditions, translating theoretical principles into real-world application, ensuring precision and effectiveness in various scenarios.